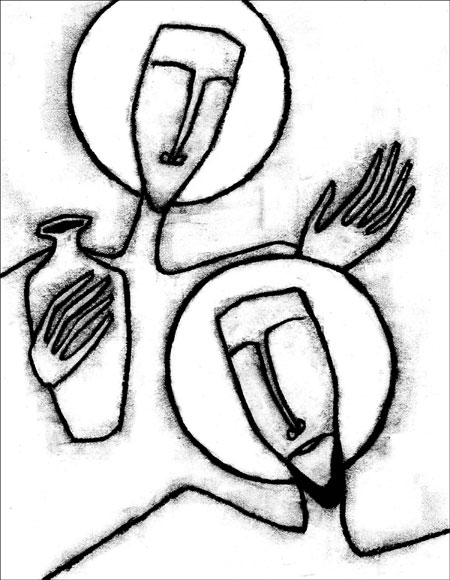

A woman, a vessel, a table, a man.

Each of the Gospels contains a story of a woman who anoints Jesus. Opinions differ as to whether these are four stories about one woman or about several. The basic elements, however, run through the stories: a woman approaches Jesus as he is sharing in a meal, and she pours precious ointment upon him—his head or his feet, depending upon which gospel you read. Jesus’ dining companions deride the woman’s action, but Jesus receives her gesture with grace. Matthew, Mark, and John place the story shortly before the crucifixion, and in their tellings Jesus acknowledges the woman’s action as a way of preparing his body for burial.

In Mark’s account, the woman breaks open her jar of ointment. Her sacramental gesture of breaking and pouring moves the story into a ritual space that contains the seeds of all that will take place over the next few days. Her action foreshadows and reverberates through the breaking of bread and pouring of wine at the Last Supper, the breaking of Jesus’ body on the cross as he empties himself utterly, the rending of the veil of the Holy of Holies in the Temple, and the opening of the tomb from which the risen Christ—still bearing the marks of his breaking—pours forth.

In no telling of the story does the woman speak. Yet her ritual action is a priestly one, and prophetic. Within her gesture echo the ancient rites of anointing: of kings, of the sick, of the bodies of those who have died.

That her gesture is also strikingly intimate is underscored by the use of a word that opens a doorway between the gospels and an ancient love poem.

Two of the Gospel writers, Mark and John, refer to the ointment the woman offers as oil of nard. Sometimes called spikenard, this costly oil comes from a plant of the valerian family that grows in the East. In the whole of scripture, the only other references to nard are in the Song of Songs. Twice the book mentions this luxuriant oil, including the opening chapter, in which the bride exults, “While the king was on his couch, my nard gave forth its fragrance.”

This tale of a woman who intimately attends to, and draws attention to, the body of Jesus is one of the stories that have fueled the theory that Jesus was married. One of the things that strikes me about the anointing story, however, is the way in which it underscores that Jesus, both as enfleshed human and as divine, was accessible to all who approached him. The question of whether Jesus was married raises intriguing and important questions about the place of the feminine in the story of Jesus. Yet I wonder if fascination with questions about whether he shared his sexuality with one specific person has been a way of deflecting our discomfort with the notion that Christ offered, and offers, his body for and to each of us. That God took flesh was a gesture of such radical intimacy that we have never known entirely what to make of it. It is mystifying that both before and after his crucifixion, Jesus manifests his solidarity with us, and his accessibility, largely through his vulnerability, a word that comes to us from the Greek vulnus. His wounds.

Yet, as we will explore later, the wounding of Jesus is all the more striking because it comes to one of such marked integrity, such completeness of being. The woman who anoints Jesus compels me with the way her being seems to match his in its integrity, its wholeness of purpose. Her power is not only that she has intuited the wounding that will come to Jesus and offers balm to him but also that her action of breaking and pouring out somehow mirrors his own. In a world in which women in particular are acculturated to be endlessly accessible, to empty ourselves constantly in the service of others, the tableau of Jesus and the anointing woman tells us: choose well where you pour yourself out.

The story of Jesus is in large part the story of how loving always breaks our hearts, how it perpetually opens up wounds within us. But that’s not the whole story, of course, for the resurrection challenges us to recognize that our wounds do not have the final word, that they can become thresholds, can become doorways into deeper and wider understandings of who we are and what God has placed us in this flesh to do.

It’s a bit of a sly move that Jesus makes, saying that the woman’s anointing has prepared his body for burial. He will no more be confined by his wounds, or by his tomb, than can this woman keep her gift confined in its alabaster jar.

Questions for reflection

Where are you pouring yourself out these days? How do you discern what to offer and where to offer it? Are you giving from the place of your deepest gifts—like the anointing woman, offering what is precious to you, something only you can give? Or are you in a place where it is difficult to give from the depths of who you are—and, if so, how is it for you to be in this place?

Adapted from Garden of Hollows: Entering the Mysteries of Lent & Easter © Jan L. Richardson.